Fundamentals of trusts

This is an exclusive series brought to you by Tax and Estate Planning advocate, Doug Carroll BBA JD LLM(tax) CFP TEP

How to use trusts in estate planning

We use the word ‘trust’ regularly in our day-to-day language. However, when it comes to its legal use in estate planning, the term ‘trust’ is likely a mystery to most people.

For centuries, trusts have been used to control, preserve and transfer property. While they may have been used more often by the affluent in the past, today the topic of trusts should be discussed in all estate planning conversations.

Trusts are a form of property ownership. More importantly, they allow for that ownership to be carefully catered to individual needs – that is, by breaking the ownership apart.

What is a trust?

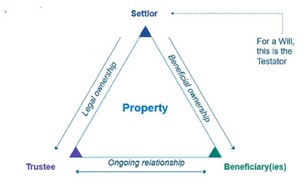

A trust is a way of separating the legal ownership of property from the beneficial ownership of property. Legal ownership is about holding title and having control, whereas beneficial ownership is about who gets to use and receive income from the property.

The structure of a trust can be represented in the familiar shape of a triangle. The initial property owner, the settlor, names a trustee as the new legal owner of the property, who holds on to the property and manages it with the obligation to do so in the best interests of the beneficiary. This is called ‘settling’ a trust.

Commonly there is just one settlor, but it is not unusual to have two or three trustees, and as many beneficiaries as circumstances require. In some situations, the settlor may also be a trustee, a beneficiary or all three.

A trust is the description of a property relationship. Specifically, it is not a legal entity but it is a taxable entity, and it is the trustee (as legal owner of the property) who is obligated to file tax returns on behalf of the trust.

Why would you want a trust?

A trust may be used when someone cannot or should not come into full ownership of property. With a trustee as legal owner, the property will still be available to the beneficiary, however it will be subject to instructions the settlor gives the trustee(s). Common uses of trusts include:

- Overseeing the inheritance of a minor child who cannot legally own property

- Insulating against creditors who may otherwise seize the person’s directly owned property

- Preserving family wealth from claims arising on a marital breakdown

- Optimizing public support for a disabled person who may be subject to asset or income limits

- Managing and monitoring charitable gifts

- Staging the distribution of inheritances down through the generations, or across blended families

- Tax planning between spouses, as well as for succession of businesses

Beneficiary rights

Sometimes a trust has one beneficiary who has all beneficial rights to the property. Alternatively, just as there are many situations where a trust may be used, there are many ways that beneficiary rights may be broken down.

For example, under a Will, you may be a primary beneficiary, or it may be contingent on someone else like a parent having predeceased. You could be entitled to a specific item, a set dollar figure or the residue that is left over. Your rights may immediately vest or may be deferred to a certain date or until some event occurs. If there are investments or real estate, you may get the income, or the capital when it is sold, or both. As well, that income may continue for a set period of time, up to a set amount, or for life.

How is a trust created?

There are legal requirements for how a trust comes into being. These are called the ‘three certainties’:

- Subject matter: Can you identify the property that is to be held in trust (either by directly naming or listing the property, or by providing instructions on how this will be done in the future)?

- Objects: Are the beneficiaries known, or is there a way to conclusively determine who they will be?

- Intention: Is it clear that the settlor wanted to separate legal ownership from beneficial ownership?

A trust can be oral, written or both, but these certainties are clearest where there is a single written trust document. If the trust is created while you are alive, it is known as an inter vivos trust, and the technical name for this document is a trust ‘indenture’. Alternatively, if a trust is created through your Will upon your death, it is known as a testamentary trust. Your Will passes your property at death to your executor as trustee of your estate. You, as the person making the Will, are known as a testator, not a settlor, but your estate is a trust all the same.

Navigating taxes

Until 2015, testamentary trusts were commonly drafted into Wills for the purpose of tax planning. Until that time, testamentary trusts were taxed at graduated tax bracket rates that progress from low to high income, similar to individual tax treatment. However, with some exceptions as noted following, they are now treated like inter vivos trusts for tax purposes, with all income taxed at the top bracket.

Graduated tax treatment is still allowed for the first three years of an estate (called a “graduated rate estate”) and for testamentary trusts held for a beneficiary who qualifies as disabled under the tax rules. Trusts can also still be used in a variety of ways to defer taxes when transferring property between spouses, whether through an inter vivos trust created during lifetime, or upon death using a testamentary trust in a Will.

Lastly, business succession planning is often driven by tax issues. In such cases, trusts do not provide a direct tax benefit, but instead have the primary purpose of maintaining control without interfering with the tax planning.

Choosing a trustee

Fundamentally a trustee’s role is to own and manage property. For a professional trustee, that is the business proposition being offered.

If instead you are thinking of naming a family member or friend as a trustee, their qualifications should be carefully considered. This includes organizational skills, financial experience and diplomatic aptitude, as well as the person’s age in relation to the expected time that the trust will continue.

Finally, as noted earlier, the trustee is required to always act in the best interests of the beneficiaries. This is known as a fiduciary duty, requiring both integrity and conscientiousness to steer clear of conflicts of interest. In other words, it is critically important that the trustee be trustworthy, in the everyday sense of the word.

Seeking Professional Guidance

This article is intended to provide a broad overview of trusts. For further information, you should speak to your legal and tax professionals to determine if this strategy is appropriate for your circumstances.

The information contained in this article was obtained from sources believed to be reliable; however, we cannot guarantee that it is accurate or complete. This material is for informational and educational purposes and it is not intended to provide specific advice including, without limitation, investment, financial, tax or similar matters.